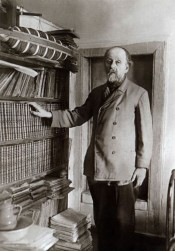

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky: moderate in his demands school mathematics teacher and a fundamentalist of contemporary astronautics

September 17, 2017, marks the 160th anniversary of the birth of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), the founder of modern astronautics, a philosopher who laid the foundations of Russian cosmism. These two vectors, which determined the movement of thought of a modest mathematics teacher from Kaluga, expose both the very scientific works of Tsiolkovsky and various sources about him, presented on the Presidential Library website. Thorough analysis of the facts from the scientist’s life, based on the evidences of the library electronic stock, lets us for another time understand and appreciate all the importance of this powerful in scholar and ethical meaning personality.

In the book by Yakov Perelman Tsiolkovsky (1932), the author denotes the main stages of the scientist’s activity and follows the origins of his genius. As you know, at the age of ten, Konstantin survived scarlet fever and lost his hearing, as a result of which he was unable to attend school and had to study independently. “While I was a child my deafness caused me inexpressible suffer, although I clearly realized that I owe to it the originality of my work, — as we can read in the above-mentioned book. What would have happened to me if I didn’t go deafen? I, maybe, did something minor, developed some kind of philosophy, maybe I would have invented something and released it, but all this would be very insignificant and doubtful, because happiness and satisfaction cancel the higher activity.”

To continue his self-education, his father decides to send a very capable for his age 16-year-old young man to Moscow. Three years of purposeful pursuits in the library of the Rumyantsev Museum enriched Tsiolkovsky with knowledge in the field of mathematics, physics and astronomy.

Life did not indulge the provincial intellectual: “I was receiving 10-15 rubles a month from home. He ate only black bread, unable even to afford potatoes and tea. But he was baying the books, the pipes, mercury, sulfuric acid and other chemical reagents for his experiments.” He did not lose this habit over the years: for 40 years he served as a teacher of mathematics at the Kaluga gymnasium, he raised seven children, and at the same time always spent part of his meager earnings, to the joy of his students, on instruments and reagents for entertaining experiments. The scientist's wife was the daughter of a priest and she tolerated their poverty without a murmur, helping her husband in everything.

The loss of hearing interfered with Konstantin Eduardovich’s full-fledged communication with the outside world, but “did not cause the decline of moral forces, — O. Kechedzhyants writes in his book Tsiolkovsky (1940), an electronic copy of which is available in the Presidential Library. — Until the end of his days, the scientist saved an unusual spiritual energy and purposefulness. Self-confidence and believe in the truthfulness of his ideas, serving which he spent his entire conscious life.”

Being still quite a young man, Tsiolkovsky wrote three studies: “Theory of gases,” “The Mechanics of the Animal Organism” and “A Continuance of Irradiation of the Stars.” He submitted these works to the St. Petersburg’s Physics and Chemical Society, which unanimously chose him as its member. Great Russian physiologist Professor I. M. Sechenov gave a good feedback on the “The Mechanics” of the hermit from Kaluga. In 1895 Tsiolkovsky published the book “An Airplane,” in which he, eight years earlier anticipating a work of the Americans Wright brothers in the field of aviation, explained the theory of the aircraft — this work was highly appreciated by the brilliant Russian scientist N. E. Zhukovsky.

His entire life of Konstantin Eduardovich was subdued to the solution of the “true state of things” on earth and beyond. In 1903 in the “Scientific Review” magazine № 5 was published Tsiolkovsky's first article on rocket technology entitled Exploration of the World Spaces with Reactive Devices. In this work, the scientist for the first time suggested a project of a liquid rocket for the actual realization of space flight, and substantiated the theory of its flight. His scientific works are widely presented in the Presidential Library: The Future of the Earth and Mankind (1928), The Project of a Metallic Airship for 40 People (1930), The Jet Airplane (1930), The Space Rocket. Experimental training (1927), The New Airplane (1929), and others.

It stands to mention that, apart from a space series, no less attention is given in the Presidential Library to the philosophical works of Konstantin Eduardovich, which made him a classic of Russian cosmism. However, in the scientist’s worldview these two spheres of science are inseparable. It is interesting that, among the works of Tsiolkovsky published in Soviet times, the works on rocket technology occupy a very modest place, mainly — it was the writings in the form of philosophical essays of an idealistic for the first look direction: The Will of the Universe (1928), Nirvana (1914), Cosmic Cause (1925), “Scientific Ethics” (1930), and so on.

“An occupancy of the universe is absolute, although not factual truth, — Tsiolkovsky writes in the last of these works. — To say that the universe is empty, that there is no life in there on the grounds that we do not see it, is a gross error. <…> Materialism in me co-existed with the belief in some comprehensible forces connected with Christ and the First Cause. I longed for this mysterious, but all these symbols that are common in all religions (“soul,” “other world,” “heaven,” “hell”) must be thoroughly worked out, decoded from the cosmic point of view.”

Here is the level of tasks that a scientist from the province set himself, in connection with which his metropolitan ill-wishers grumbled that this “upstart” puts himself above God. But this is not true: “I always remembered that there was something unsolved, that the Galilean teacher still alive and significant, still has influence.” Tsiolkovsky was a materialist, but not a Marxist positivist. He was tormented by the “awareness of the incompleteness of science, the possibility of error and human limitations, very far from the true state of things. It is still remains today and even grows with the years.” As we can see, his persistent desire to interpret from the scientific point of view the system of truths of religion only grew with time.

From his essay The Cause of the Cosmos: with the addition of a review of the “Monism of the Universe” and answers to questions about this book (1925), Tsiolkovsky continues his argument with his opponents: “I would like to exalt you from contemplating the universe, from the fate that awaits you all, from the wonderful history of the past and the future of every atom… My conclusions are more consolatory than the promises of the most cheerful religions. No one positivist can be sober than me. Even Spinoza is a mystic compared to me, if my wine is intoxicating, it is still natural.”

The dispute is not over, so in recent decades, interest in Russian cosmism, its philosophical and general cultural heritage has been steadily growing. This is evidenced by a number of dissertations of our contemporaries, for example, the digitized abstract of Vladimir Lytkin for the title of Doctor of Philosophy Philosophical and Anthropological Project of K. E. Tsiolkovsky (2013), where the author writes: “Already at the beginning of the XX century Tsiolkovsky, like other cosmists, saw the enormous importance that global threats can have in the future for mankind: ecological catastrophes, cosmic cataclysms, a depletion of raw materials, etc. To solve these and other problems, Tsiolkovsky approached with anthropological point of view, so he can be considered the founder of the anthropology of space, the objective of which is studying the possible forms of life in the universe, studying the cosmic future of mankind.”

“The Kaluga dreamer” quite obviously promised in his philosophy to warm the humanity up, giving it a confidence in eternal life into a pulsating infinity.